I was recently diagnosed with a neurological disability and I’m still trying to come to terms with it. (Photo courtesy: Louis Lim)

Twenty years later—and my fourth attempt at higher education—I was exhausted, consumed by a cycle of stress that I didn’t yet understand.

I struggle with depression, shame, and anxiety.

Looking for answers, I consulted a psychiatrist, who suspected I might have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

This was the first time anyone had suggested that my brain chemistry might be responsible for the challenges I was facing.

As an artist, I thought I was just absent-minded and dreamy. I hid my struggles by staying busy. (Credit: Timothy Fairless)

For decades, I was convinced by the stereotype of the Asian work ethic that I just had to work harder.

I thought my difficulties were personal flaws, and I didn’t realize how much fun was being taken away from my life.

I never thought a chemical imbalance could be the culprit.

Doing life on hard mode

Anything that could be done freely required more effort from my brain, but until I was diagnosed, I couldn’t figure out why.

I told myself that everyone procrastinates.

Secretly, I was having a hard time completing seemingly simple tasks: chores, making a quick phone call, and meeting deadlines.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always had a hard time asking for help, and also having a hard time accepting it. (Image credit: Supplied)

Coming from a culture that values determination and a strong work ethic, I saw myself as a failure; someone who lacked the desire to achieve my goals.

This was not the case, but I felt sad, helpless, depressed, and escaping reality. I hid my struggles by keeping myself busy with other things.

Learning more about ADHD helped me understand what was going on in my brain.

I spoke with Caitlin and Emma Hughes, the founders of Cathartic Collaborations, a practice that provides therapy services to neurodiverse people in Maganjin.

Caitlin and Emma Hughes know what it’s like to have ADHD, and they both use their work to help others with the disorder. (ABC News: Mark Leonardi)

Caitlin, a certified mental health social worker, likens life with ADHD to playing a challenging video game.

“It’s like living on hard mode .. everything is more difficult,” she said.

So, what is ADHD?

Associate Professor Savio Sardinha is a Yugambeh (Gold Coast) Psychiatrist.

He explained that people with ADHD experience symptoms such as inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity, which can manifest in different combinations and affect all areas of their lives.

In my experience, these symptoms can be quite severe.

loading

I definitely don’t look like the stereotype of ADHD: a naughty school-age boy – restless, disruptive and distracted.

Most people would say I am polite, have a good memory, and that I am diligent and detail-oriented.

After four different attempts at higher education, I graduated in 2022 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts. (Provided)

So it was no surprise that those closest to me didn’t recognize my challenges.

I was constantly overwhelmed by the fact that I had the ability but not the mental ability to do the things I wanted to do.

But I later learned that these setbacks are common for people with ADHD.

The experts I interviewed advocate for greater awareness of ADHD, particularly in the areas of education, medicine, and policy.

This is because the situation is complex – and my own gaps in knowledge help hide invisible disabilities.

During my studies, I kept a journal of how frustrated I felt: day after day of frustration, sadness, and anxiety. (Supplied)

The complexities of identity and ADHD

I thought I had it all under control, so I kept these challenges to myself. But they were out of my control.

I couldn’t hide it anymore, I broke down.

I mistakenly believed that I should be able to solve my problems on my own and struggled to come to terms with my experiences.

Combined with the behaviors I inherited from my mixed-culture upbringing, I didn’t know how to ask for help, nor how to accept it.

My family members were deeply distressed to see me in this state.

Emma Hughes uses her background in management and business operations to help other queer and neurodiverse people. (ABC News: Mark Leonardi)

I can relate to Emma’s description of her experience with ADHD:

“You’re always trying to .. be better, do better, always chasing something that you can’t catch because, unfortunately, it’s more than your brain can handle,” she said.

Currently, the condition is viewed as a problem to be solved; clinical involvement and diagnosis are viewed as the solution.

So, I did just that.

Is ADHD a disability?

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in the country, yet according to the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP), the condition “remains underdiagnosed and undertreated).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) affects the nervous system, making it more difficult to regulate emotions and executive function.

But is this a disability? It depends on who you ask.

Caitlin Hughes has a neurodiversity disorder and believes in tailoring treatment to the individual patient. (ABC News: Mark Leonardi)

“One of the interesting things about ADHD is that, even though it can be quite disabling, it’s not actually considered a disability in the NDIS,” Caitlin says.

“They don’t offer support for ADHD because it’s a treatable condition.”

Now that I understand how my brain works, I can find strategies to make life easier – and writing down my feelings helps clear my mind. (Credit: Claudia Baxter)

Government data shows the use of psychostimulants to treat conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has continued to grow in recent years.

Dr. Sardinha theorizes that the restrictions of the COVID-19 lockdown “may have exposed many of the ADHD behaviors”.

“It’s likely that these environmental factors contribute to more pent-up energy and unchecked behavior, especially in children,” he said.

Because neurology and genetics haven’t changed much since the outbreak, social norms and culture are driving the diagnosis, he said.

“A fair criticism is to say there has been an increase in (recognized) behaviors, but not necessarily an increase in prevalence,” Dr. Sadinha said.

“Certainly, on the contrary, because of the increased awareness .. people are seeking more help and, therefore, there are more diagnoses.”

So while it may feel like more people are suffering from ADHD, what’s actually changing is our understanding of the disorder.

Intersectionality

Art and storytelling help me find ways to express myself as a person with ADHD. (Image credit: Thomas Oliver)

Mental health classifications are based on an individual’s symptoms, but Dr. Sadinha said cultural factors can influence how the disorder manifests in people from different backgrounds. This can differ from the Western understanding of ADHD.

He said research had found some Aboriginal groups in Western Australia had greater acceptance of ADHD, the main symptom of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“Because of a higher tolerance for ADHD in this group, it may be going underdiagnosed,” he said.

Cathartic Collaborations has stimulation items for people with ADHD, similar to fidget toys, like this sequined blanket. (ABC News: Mark Leonardi)

This may be why I didn’t develop ADHD early in life – I never saw myself in the context of ADHD.

My identity as a gay man added another layer of intersectionality, which probably further fueled my desire to cover up.

“In neurodiverse spaces, there are often more gender and sexual orientation diverse people,” Caitlin explained.

“I would say that a lot of people with ADHD do have this intersectional experience.”

She said life as a neurodiverse person can be “quite painful,” and criticism of a person’s sexual orientation or culture only exacerbates that pain.

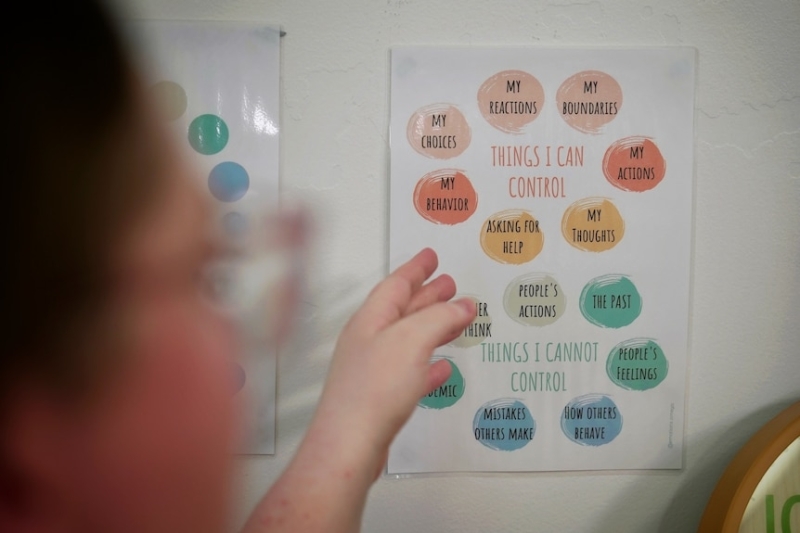

Learning to accept what I can and cannot control has helped me manage my ADHD. (ABC News: Mark Leonardi)

Caitlin said neuroaffirmative therapists can help provide a safe space, while Emma said it’s important to make this approach known so that different sufferers can find a place where they feel welcome.

In its 2023 submission to the Senate Inquiry into ADHD, the RANZCP noted: “Culturally and linguistically diverse people also have complex needs and barriers to receiving diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

The RANZCP also recommends that ADHD be included in the NDIS “as an eligible psychosocial disability”.

I think it’s a great idea, but most of all I want people with hidden disabilities to be kind to themselves – life in “hard mode” is what it is, so be kind to yourself and find what works for your specific situation.

International Day of People with Disability

The photo shows a dark blue human figure on a cream background with orange, blue and green swirls.

Please visit the IDPwD website to find out how to get involved this year.

This article is part of the ABC’s coverage and commemorations of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities (IDPwD).

Mark du Potiers is a visual artist born, raised and living in Maganzinar (Brisbane), Queensland, of Australian, Hong Kong and Chinese descent. He was diagnosed with ADHD in his 30s.

Read more stories from the 2024 IDPwD campaign, celebrating the contributions and achievements of 5.5 million Australians with a disability.

This story was contributed by Gemma Ferguson.