Australia imports most of its coffee from Brazil, Colombia, Vietnam and Honduras. (ABC News: Jarrod Fankhauser)

In Australia, where coffee culture runs deep, consumers have been warned the price of their morning latte could rise to $8 or even double digits.

The root of the problem can be traced to the other side of the world.

Brazil — the world's largest producer of Australia's favoured coffee bean arabica — has faced extreme weather in recent years, including droughts, excessive rainfall, and temperature shifts that have slashed harvests.

"Exporters aren't hoarding coffee to inflate prices," said Candy MacLaughlin, a coffee grower and industry expert.

"There's a genuine shortage looming because supply isn't keeping up with demand."

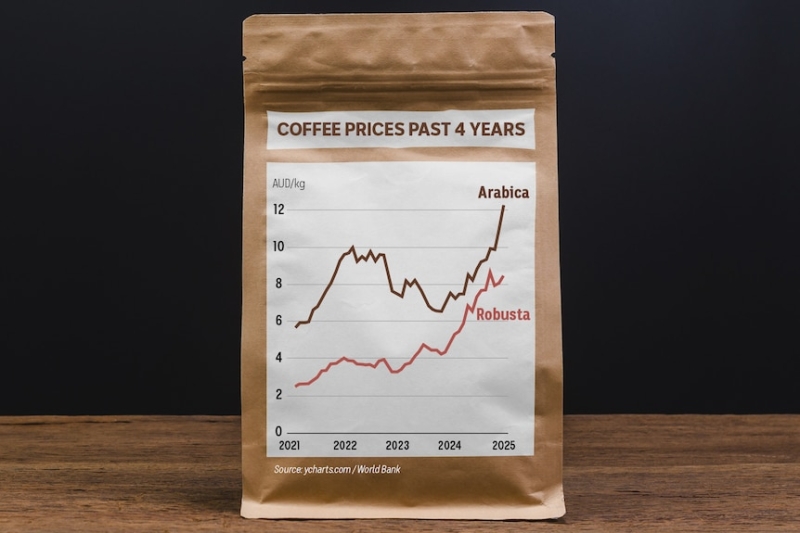

Global coffee bean prices have soared in recent years. (ABC News: Jarrod Fankhauser)

This has led Brazil's green arabica coffee bean prices to rise by 112 per cent in 2024, according to traders, with flow-on effects to all types of coffee.

In 2022, Australia sourced most of its coffee from Brazil, followed by Colombia, Vietnam and Honduras, according to UN data.

And while Australia is surrounded by coffee-growing countries like Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, and Vietnam, Caleb Holstein, co-founder of coffee roasters Greensquare, explains that "it's not as simple as going to a different origin for a better price".

'Scaling up is hard'

In Indonesia, the world's fourth-largest coffee producer, farmers like Eti Sumiati of Satrea Wanoja coffee are striving to improve quality and yield.

"I started with 20 hectares and six people in a cooperative," said Ms Sumiati.

"We pick and process everything by hand to ensure quality, but scaling up is hard."

Intan Taufik, a fermentation expert at the Bandung Institute of Technology, is helping Indonesian growers remove unwanted microbes during processing.

He points to another reason why Australians aren't looking closer to home to source more of its coffee.

Taiwan, once famous for bubble tea, now brewing its path to coffee fame

Photo shows A man serves coffee in a shop

"Australians don't like some of the traditional spicier flavours we have here," he said.

But Fawad Ali, a sustainability researcher at Griffith University, sees specialty coffee as the most promising path.

"We're researching ways to create natural profiles that align with consumer tastes," he said.

"The biggest achievement for the sustainability of the coffee industry [would be] to attract more growers, increase the number of trees and improve production."

Timor-Leste is an up-and-coming coffee producer amid global supply shortages. (Supplied: Troy Huckstepp)

Timor-Leste, meanwhile, is still building its coffee industry after decades of neglect.

"Most farmers own less than two hectares of land and don't use fertilisers or pesticides," said Miledis Lopes, a manager at coffee producer and exporter Orijem Timor.

"Low yields make it hard to reinvest in better methods."

Timor-Leste farmers hope to bring more specialty coffee to the world. (Supplied: Troy Huckstepp)

She noted that yields were about 10 per cent of the global average due to limited knowledge and technology.

Troy Huckstepp, founder of Orijem Timor, said the country had untapped potential.

"We're trying to break the cycle of only producing commodity-grade coffee," he said.

"But it requires knowledge-sharing — teaching farmers how to prune trees properly, plant shade trees, and adapt to a changing climate," he said.

Vietnam's role and its limitations

Vietnam, the world's largest robusta producer, faces unique constraints.

One reason is taste.

Nguyen Thi Tran Chau Ngoc says constant changes in weather are affecting her crops. (Supplied: Nguyen Thi Tran Chau Ngoc)

Australians overwhelmingly prefer arabica beans for their smooth, complex flavours, while robusta — Vietnam's primary export — is often described as "woody" or "rubbery".

"It's not something Australians are used to drinking, except in instant coffee blends," said Jeff Carlin, a veteran coffee roaster.

The government has limited the expansion of coffee-growing areas for over a decade to curb deforestation.

"Even if demand rises, Vietnam can't simply expand its output," said Carlos Mera, a commodities trader at Rabobank.

Why your flat white is going up, no matter where you live

Photo shows Close up of flat white in coffee cup with $5.50 in change

At the same time, robusta prices have soared.

"Vietnam's coffee prices went bonkers 18 months ago as importers scrambled to switch to cheaper beans," said Mr Carlin.

Vietnam, like Brazil, has also endured extreme weather in recent years.

"Every day, we see the climate changing with more rain," said Nguyen Thi Tran Chau Ngoc, a grower in Vietnam.

'It's not easy for us'

Papua New Guinea grows arabica coffee in its volcanic soil, but faces major hurdles as it tries to scale up.

In its rugged highlands, Prisilla Manove walks through her family's coffee garden, a legacy of generations of smallholder farming.

"I grew up on a plantation, picking coffee and processing it," said Ms Manove, who runs a social enterprise Blue Mama Commodities helping local farmers.

"Now, the prices are the best we've seen in years, but it's still not easy for us."

Older coffee trees in PNG are more susceptible to diseases and pests. (Supplied: Priscilla Manove)

Ms Manove and other coffee growers continue to face challenges capitalising on high coffee prices, including aging coffee trees, lack of infrastructure, and an absence of investment.

"Most of PNG's coffee trees are aging and producing lower yields," said Ms Manove.

"And when coffee prices were lower in past years, many farmers turned to other crops like fruits."

Still, Mr Holstein and others believe PNG, once dismissed for poor quality, is undergoing a renaissance and could provide more production in the future

"Ten years ago, PNG coffee was seen as untouchable," said Mr Holstein.

"Now, there's been some investment from major trading houses and we're seeing PNG beans match Colombian and Kenyan profiles in certain blends."

A partnership with Australia's Department of Primary Industries is tackling diseases like leaf rot and the berry borer pest.

Yet infrastructure remains a major hurdle, as does crime and weak governance.

Transporting coffee from Goroka in the highlands to the port at Lae often costs as much as shipping it overseas.

"Road access is frequently damaged by heavy rains, and washed away," explained Jeffrey Neilson, an associate professor of economics at the University of Sydney.

Small landholder farmers in Timor-Leste are finding it difficult to scale up their production. (Supplied: Troy Huckstepp)

The Asia-Pacific boom

On the demand side, new markets are emerging, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region.

Coffee consumption is booming in Asia. (ABC News: Jarrod Fankhauser)

Mr Holstein pointed to China, where coffee was once considered a niche product.

"China went from the 20th-largest consumer of Brazilian coffee to the sixth in about 12 months," he explains.

This spike in demand has created an unprecedented squeeze on supply.

A massive player from China, Luckin Coffee, recently signed two historic deals with the Brazilian Coffee Board.

Luckin Coffee and others in Asia have placed massive coffee bean orders from Brazil. (ABC News: Jarrod Fankhauser)

The first deal in June was for 120,000 tonnes of coffee worth $US500 million ($805 million).

Then, just four months later, they doubled the volume — but the price had jumped to $US900 million for the same amount.

"That's a $US2.60 per pound commitment, compared to the $1 historically paid by Western buyers," explained Mr Holstein.

The path forward

With demand outpacing supply and climate change reshaping growing conditions, the coffee industry faces a precarious future.

By 2040, the world may face a robusta coffee shortage of up to 35 million (60 kilogram) bags due in part to climate change and consumption trends, according to the NGO World Coffee Research.

Fresh coffee cherries ready for processing in Timor-Leste. (Supplied: Troy Huckstepp)

"There hasn't been enough investment in planting or infrastructure," said Mr Carlin.

Ms Manove, for her part, remains optimistic.

"The world loves coffee, and we can grow some of the best," she said.

"But we need the tools and the knowledge to keep going, as a lot of that was lost when plantations broke into smaller holders of land."