Christos Tsiolkas, bestselling author of The Slap, Barracuda and The In-Between, is one of the artists supporting Save Our Arts ahead of the federal election, which is due to be held on or before May 17. (Supplied: Allen & Unwin/Sarah Enticknap)

When Christos Tsiolkas was writing The Slap, he was working as a veterinary nurse.

"I was in between jobs and my friend, who's a veterinarian, suggested I work for him for a few months until I got back on my feet," he says.

"It gave me the space to write."

Before he became a veterinary nurse, he worked as a film archivist, removalist, administrator and cleaner, all while writing on the side. He released three novels between 1995 and 2008's The Slap.

That book — about a group of people at a barbecue whose lives are changed by the slap of the title — won a slew of awards, became an international bestseller, and was adapted into an Australian TV series in 2011 and an American one in 2015.

It was only after that book's success that Tsiolkas — in his late 40s and 20-odd years into his writing career — could make a living out of writing.

"The Slap gave me, for the first time in my life and for the first time in my partner's life, financial security that we never had before."

The sheer difficulty of making a living as an artist is just one of the reasons Tsiolkas is one of the creatives supporting the Save Our Arts campaign, alongside others including playwright Suzie Miller, actor Rhys Muldoon, and authors Tim Winton and Charlotte Wood.

Suzie Miller, one of the supporters of Save Our Arts, won best new play at the 2023 Olivier Awards for Prima Facie. (Supplied: Sarah Hadley)

The campaign — which is not led by any arts body, but by a disparate group of organisers who are passionate about the arts — hopes to put arts policy and funding onto the agenda ahead of the upcoming federal election.

It's the successor to Fund the Arts, which ran ahead of the 2022 federal election, and contributed to the government's as-yet-unfulfilled commitment to local content quotas for streamers, and $280 million in additional arts funding.

Culture at a crossroads

Academic and Save Our Arts policy adviser Dr Ben Eltham says Australian arts and culture is "at a crossroads".

"We're seeing lots of trends away from Australian art and culture and content and towards international tech giants, tech billionaires, making the decisions about the sort of music, art, literature, culture, that local audiences get to see and enjoy."

Last year, Charlotte Wood, a supporter of Save Our Arts, was the first Australian shortlisted for the Booker in 10 years. (Supplied: Allen & Unwin/Carly Earl)

He points to music and screen-streaming services such as Spotify and Netflix as examples. Unlike local broadcasters, they do not have to meet Australian content quotas.

"The risk here is that we're going to end up back in the kind of 60s, back in the era before Whitlam, where Australian culture was an outpost; where all the decisions were made in foreign capitals by foreign corporations; and where, for Australian artists to have a career, they have to leave Australia," Eltham says.

"And you're already seeing a lot of Australian artists, particularly musicians, moving to say, LA. Because that's where the industry is."

Amyl and the Sniffers are among the Australian artists who have moved overseas to build their careers. (Supplied: Virgin Music/John Angus Stewart)

It's a stark shift away from what Eltham describes as a kind of Australian cultural boom in the 00s.

"It's a real shame, and it's a real worry," he says.

"There was a period when you could almost say Australian art and culture was taking over the world.

"You had these incredible actors moving to Hollywood and smashing it. You had Australian novelists winning the Booker. You had Australian music getting massive all over the world. You had Australian visual artists being internationally influential."

What does Save Our Arts want to see happen?

Save Our Arts wants to revitalise Australia's cultural industries through the creation of 200 creative fellowships for emerging artists; an extra $10 million for the Translation Fund for Literature; and $5 billion over 10 years for a cultural infrastructure fund for Australia's galleries, theatres, cultural hubs and libraries.

Save Our Arts was inspired to advocate for the establishment of more creative fellowships by universal basic income for artists in Ireland. (Pictured: Save Our Arts supporter Tim Winton.) (Supplied: Denise Winton)

The collective intends to campaign in federal seats during the election, through social media and community outreach, putting pressure on political parties to adopt its suggested initiatives.

The campaign would like to see the government legislate an AI Act to protect the copyright and intellectual property of Australians, including a stamp that clearly shows a work has been "Made by Humans".

"That's the sort of thing that actually could be pursued by government, and that governments already do with other types of accreditation and labelling, for example, of organic produce in the agricultural sector," Eltham explains.

"We were told that AI would do the drudgery work, and it would free us up to have more free time. Instead, what it seems to be doing is stealing the jobs of artists and making billionaires richer."

Save Our Arts also advocates for a quota of 20 per cent Australian content on streaming platforms, with streamers who fail to meet that quota paying a levy that would fund arts and cultural projects. In addition, a "Koala stamp" would indicate Australian content on Spotify and Netflix.

In 2021, the Bureau of Communications, Arts and Regional Research found Australian movies and TV shows accounted for less than 2 per cent of Netflix's local catalogue. (Pictured: Anna Torv in Netflix's Territory.) (Supplied: Netflix)

The final request is for production offsets — as used in the screen sector — to be extended to other areas of the arts, specifically for new Australian work, and for an insurance fund for the music and performing arts industries.

"You get a production offset for making a TV show or movie in Australia, but you don't get anything at all for putting on a festival," Eltham says.

"The music industry has got a big insurance problem, and rising costs. But they also have falling audiences, and one of the problems there is that local audiences don't want to go to see local acts. Why? Because they don't know about them."

Falling audiences can also be linked to the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, he says, with many Australians struggling to make ends meet.

"I would argue that it's even more important in a cost-of-living crisis that governments step up to provide culture free of charge," Eltham says.

"It's why public art is so important; public culture; public libraries."

Giving back

Tsiolkas says it's much harder to sustain yourself as an artist now than when he was starting out.

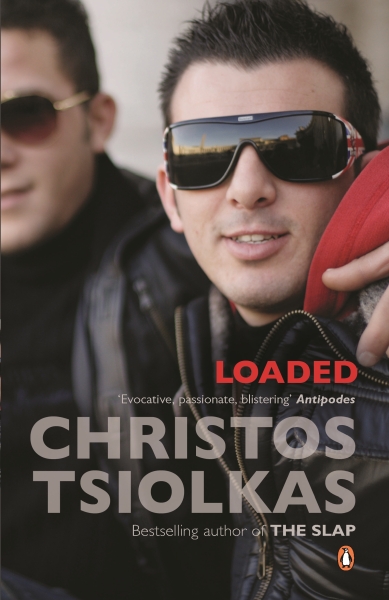

The first print run of Loaded was 6,000. When the film adaptation Head On premiered in 1998, the book's sales went up to more than 30,000. (Supplied: Penguin)

"I feel like I'm part of a really lucky generation," he says.

"These days, housing is so much more expensive, health is so much more expensive, and education is so much more expensive."

Tsiolkas benefited from government support at the beginning of his career. His publisher, Vintage Books, received a publishing subsidy of $2,718 towards production costs for his first novel, Loaded (1995), and, eight years later, Tsiolkas received a Literature Board Grant for Established Writers.

"It was important to get support, whether from grants or from organisations like Writers Victoria. They took what I wanted to do seriously and were able to help with the matter-of-fact things, like paying your bills, paying rent or the mortgage, paying the groceries," he says.

"We need to make it so people are not worried how they're going to pay the grocery bill every single day of their life.

"Because if you're doing that, you're not writing, you're not making films, you're not painting."

He says the issue of subsistence for artists is tied to class — and who gets to make art.

"[We] need to take class seriously," Tsiolkas says.

"One of the things that's hardest to fight against is a notion that being an artist or being a writer is a really bougie thing; that it's something that only a certain group of people in society can do.

"That's absolutely not true, but it is a lot harder to do if you come from a working-class background, or you come from communities that have been, for a long time, ignored or under-represented in the arts."