A single, Indigenous woman in 1971 changed her mind about adopting out her son. She believes she was deliberately deceived

It was through a cafe window that Patsy Brown finally glimpsed the man she’d thought of every day for 22 years.

He pulled up on a motorbike on a busy street in Brisbane’s inner-south, removing his helmet to reveal long dark hair and bright blue eyes.

This, surely, must be her son.

Patsy has rarely spoken about the heart-wrenching circumstances that separated her from her first-born child for two decades, but at 73, she says there is a kind of catharsis that comes from telling her story.

“I thought that opening up might help me,” she says.

“There’s still the guilt that lingers. And the regret.”

The Quandamooka woman had hoped to give evidence at Queensland’s truth-telling and healing inquiry on Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) late last year, until the LNP dismantled the process five months after it began.

Patsy says she feels as if things are “going backwards” when it comes to understanding the issues affecting Indigenous people.

“There are people who just don’t care,” she says.

“They say ‘It’s the past, you’ve got to get over it’ … but you can’t get over it until you’ve actually talked about it and had people empathise with you.”

Patsy recalls the first meeting with her adult son as she sits in a cushioned wicker chair on the veranda of her home on Minjerribah, off the coast of Brisbane. Her house is surrounded by scrubland, and is a short stroll from the turquoise ocean. The bush is alive with cicadas. A warm breeze carries the scent of eucalyptus along the shaded wooden deck.

Patsy built this place a year ago, shortly after returning to the island she grew up on.

“You’ve got to die on country, you know?” she says.

She remembers an idyllic childhood with her 12 younger siblings, bathing in creek water and eating wild fruits and freshly-caught eugaries (pippies) by the light of a kerosene lamp.

They grew up at a place called One Mile – named for its distance from the nearest township of Dunwich. This was the era of segregation, when Indigenous people lived under strict controls on missions and reserves, but Patsy didn’t know that yet.

She would learn about discrimination later in life. She would learn that her father had been taken from his family as a small child and raised in an orphanage, unable to speak about the experience before his death at the age of 46.

But perhaps Patsy’s harshest lesson would come when she was 20.

In 1971, living on the mainland and juggling jobs nannying for a large English family and waiting tables at Brisbane’s Treasury Hotel, she became pregnant.

Her partner didn’t want the baby. She had no savings and her parents still had eight of their own children at home.

Unable to see another option, Patsy checked in to the Boothville Mothers’ hospital, a maternity home primarily for single women run by the Salvation Army. She decided to put her baby up for adoption, believing the child would be “better off” with two parents.

But she had no idea what awaited her at Boothville.

Pregnant, she was put to work in the laundry, cleaning the soiled sheets of the married women. Medical records show Patsy was twice hospitalised with high blood pressure – “because of the hard work,” she says.

On Friday nights the unwed mothers-to-be attended “Salvationist classes”.

“They said – it’s etched in my mind – ‘Get down on your knees, you sinners, and ask God for forgiveness’,” Patsy recalls.

Other women have shared similar stories of being shamed, put to work and traumatised at Boothville while single and pregnant.

Around 48 hours in to her labour, as Patsy groaned and panted, she was told: “Be quiet. Stop making so much noise.”

Later, as she held her baby boy, she remembers being awestruck by the little hands.

“That was a picture in my brain all my life. I remember the shape of his hands and his fingers.”

The days after the birth passed in a blur. She remembers someone from the child protection department asking her to sign an adoption agreement. After about a week, Patsy went home, leaving her son behind.

“Emotionally and psychologically, there was really no preparation, no discussion about adoption,” she says.

“The question was, ‘What are you going to do with your baby? Are you putting your baby up for adoption?’ And that was it.”

She tried to resume her nannying duties, but felt heartbroken.

“I was just miserable, you know? I was crying all the time,” she says.

Encouraged by her employer – who assured her she could keep her job and her baby – Patsy called the hospital two weeks after giving birth, telling the answering nurse she had made a mistake and was coming to collect her son.

“She said, ‘Well, it’s too late. He’s already gone.’ Those were her exact words,” she says.

Unbeknownst to Patsy, it was not too late. Under the 1964 Queensland Adoption Act, parties could revoke their consent within 30 days of signing an adoption agreement, or before an adoption order was made (whichever came first).

Government documents show Patsy’s son was born in April, but not officially adopted until October.

Patsy now believes this information was deliberately withheld from her.

Children were routinely taken from unwed mothers – Indigenous and non-Indigenous – from the 1950s to the 1970s in a practice known as forced adoption.

In 2012, a federal inquiry into the practice found information was often withheld from single mothers, including their right to revoke consent for adoptions. Its report mentioned Boothville as an institution where forced adoptions took place.

A decade later, the Salvation Army apologised for its role in Australia’s forced adoptions policy and the continuing effect it has had.

After the birth of her son, a broken-hearted Patsy moved north, living a “reckless” life before settling down to have two more children: another son, and a daughter.

But her first-born was never far from her mind.

“Not a day went by where I didn’t think about him,” she says. “Just looking for him in a crowd, imagining how he might look.”

Patsy believes her son would have been about 15 when she opened up about the ordeal to a social worker friend, who told her the crushing news that she had been entitled to change her mind about the adoption.

“It just felt, you know, can my heart take any more?” she says.

Legally she had to wait until her son was 21 to receive information about his whereabouts.

Even then, it took a year to build up the courage to write a letter to his adoptive parents.

“I was terrified that he might be dead. And then, if he weren’t dead, that he might reject me,” she says.

Two days later, Patsy got a response: her son, Shannon, was happy to meet.

When she greeted him with a quick hug, she felt his body tense.

“Don’t worry – I’ll get used to it,” he told her.

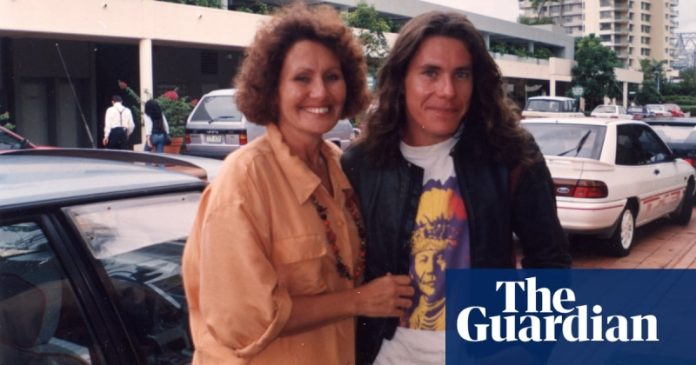

The pair would go on to enjoy barbecues in the park, long phone calls and regular visits as Patsy’s eldest son was welcomed into the family fold.

For Shannon, meeting his extended family was “fantastic” – if a little daunting.

“It’s a huge family,” he says.

“It was hard to remember all the names. I’ve had to put them all down on a spreadsheet to keep track.”

But in those first tentative moments at a Brisbane cafe, as Patsy Brown grasped for a way to fill a 22-year chasm, one familiar detail brought her comfort.

“I remember touching his hands and holding them and looking at the palms, and then turning them over and looking at his fingers,” she says.

They had grown since she last held them, but their shape was just the same.