The peak body for overseas aid organisations said without intervention, the consequences of the president’s decision ‘will be catastrophic’

Australian overseas aid programs could shut, causing “unnecessary deaths and suffering”, in the fallout from the Trump administration’s decision to freeze foreign aid.

Workers have described “chaos” and “total panic” as they try to work out what the policy means. The peak body for overseas aid organisations said without intervention, the consequences of the move “will be catastrophic”.

The United States provides about US$68bn in foreign aid a year, more than 40% of global humanitarian funding. Most of it is managed by the US Agency for International Development (USAid).

Under president Donald Trump’s orders – one of dozens he signed after being re-elected to the White House – the funding dried up for an initial period of 90 days, with some exceptions for emergency food aid, and military funding for Israel and Egypt.

USAid staff were issued “stop work” directives, and banned from discussing the situation without approval. Funded organisations were also ordered to stop work on all contracts, grants, agreements and programs.

Elon Musk, who now runs the US government’s “department of government efficiency” (Doge), said the government was working to shut down USAid altogether with Trump’s approval. On Tuesday, the administration confirmed it would shrink USAid and merge it with the state department.

A range of Australian projects have USAid funding. Some organisations receive funds directly, while others work on projects that are jointly funded by the US and other partners and it is unclear what the stop work orders mean for them. There are concerns the US has left a chasm that could be filled by China.

The Australian Council for International Development (Acfid) is the peak body for non-government organisations (NGOs) working in international development and humanitarian projects.

Acfid interim chief executive officer, Matthew Maury, said funding for climate crisis work, food, health, infrastructure and disaster programs were at risk.

“This disruption will have wide-reaching impacts, interrupting critical life-saving work, including access to food for families, basic education for children, safety for women fleeing sexual and gender-based violence, and providing medications to children and others suffering from disease,” he said.

“Australian aid organisations with USAid-funded projects are at risk, as implementing partners rely on USAid funds for part of their operating costs. This could force organisations to shut down, with some already forced to let staff go.”

Maury said NGOs were “deeply concerned about how the immediate gaps will be addressed and the impact on communities that have relied on aid for essential services” including healthcare, education and basic necessities such as clean water.

“Without intervention, the consequences will be catastrophic. We are talking about unnecessary deaths and suffering.

“Initial data suggests that over AUD$256m worth of programs delivered by Acfid members and partners globally will be impacted, with $119m of funding impacted in the Pacific alone. These are programs at risk of not continuing,” he said.

Trump has ordered efficiency reviews be done on all US-backed programs.

He wrote in his executive order that the “foreign aid industry and bureaucracy are not aligned with American interests and in many cases antithetical to American values”.

Last week, the administration granted a waiver for “life-saving humanitarian assistance” but it is not clear what that covers.

Guardian Australia spoke to a range of organisations that declined to be named for fear of retaliation. Several major NGOs referred inquiries to their US headquarters.

The Australian International Development Network (Aidn) warns the policy threatens lives, and is meeting with US foundations to work out where the most urgent needs lie.

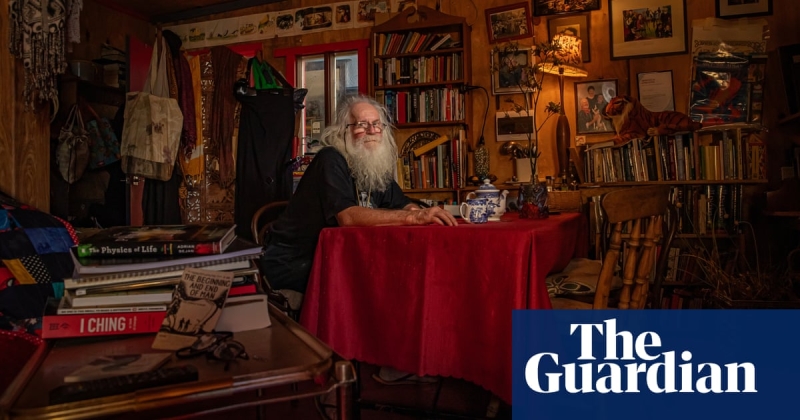

Mark Cubit co-founded Aidn, which describes itself as a collaboration of private sector individuals, philanthropists, organisations, donors, businesses and government.

Cubit confirmed people and organisations will not speak out for fear of losing funding altogether, but said Aidn does not rely on USAid funding.

“Organisations who received a sudden communication that everything must stop are left dealing with the implications of that – initially having to tell their staff,” he said. “The second obvious effect is on the beneficiaries.

“If it’s child literacy programs that’s unfortunate. If it’s the provision of tuberculosis medication it’s life threatening.”

Cubit said Australian charities would not be able to pick up the slack without more funding from external parties.

He said he was not optimistic the Australian government would increase its foreign aid to help.

“Australia is one of the stingiest aid funders, so it will be up to the private sector and China to pick up the slack,” he said.

“China will bring issues, obviously.”

A spokesperson for the foreign minister, Penny Wong, said the decision was a matter for the US administration and that Australia’s development program was “focused on being a partner of choice for our neighbours”.

The Australian founder of the Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation, Michael Brosowski, who’s organisation rescues victims from slavery and human trafficking in Vietnam, said only 10% of their funding came from the US, so they would have to scale back but were not at risk of closing.

“It’s a pause, and we don’t know what will happen next,” he said.

“Part of the disappointment with this is that the US government has absolutely stood out as the world’s leader in anti-trafficking, and I hope they don’t lose that now.

“It’s not clear if anyone else can step up to take the place of the US.”

An aid insider in Myanmar who has worked for Australia said it was “total chaos” there when anyone who received US funding got a letter demanding they cease all activity. He said programs and projects with funding from the US and Australia were struggling to work out what they could do.

“Even if you think you can continue 60% of your activities, the fear is that will also be contrary to the order, so that makes it incredibly uncertain,” he said.

The Australian head of a south-east Asian organisation said people were “absolutely panicking” but had been told not to speak publicly. “People are terrified they’re being monitored,” he said.

“It feels like an ideological attack.”

He said he imagined regional governments would be on the phone to China, to fill the void and challenge America’s leadership in the region.

“People are really angry … it’s going to be really hard to trust America again,” he said.