John Stonehouse was a British Labour Party politician until he faked his own death and moved to Australia. (Getty: Chris Wood/Daily Express/Hulton Archive)

On November 20, 1974, John Stonehouse was on a business trip in the United States when he vanished after going for an afternoon dip in the Atlantic Ocean.

The British backbencher turned businessman had travelled from the United Kingdom to Miami with long-time friend and barrister, James Overton Charlton, to meet with American bankers and discuss a business opportunity.

But things took a turn when Stonehouse failed to show up to dinner one evening, an unusual occurrence that prompted his colleague to become concerned and ask staff to check his hotel suite.

A search of the room didn't uncover anything out of the ordinary, with Stonehouse's belongings carelessly strewn about like a man who had stepped out and planned to return momentarily.

His watch lay on the bedside table along with other important documents, including his passport and $US800 in cash and traveller's cheques.

These were not items one would typically leave behind if they weren't planning on coming back. But as the hours ticked by, John Stonehouse was nowhere to be found.

Witnesses claimed they had spotted him that afternoon on Miami Beach, dressed in board shorts and walking out to sea.

His neatly folded trousers and patterned shirt were later found abandoned on the counter of a small beach hut, indicating the promising British MP had gone for a swim and likely drowned in the Atlantic.

Presumed dead without a body, newspapers began reporting the circumstances of his fatal misadventure in Florida.

But the Labor politician wasn't dead.

The deserted clothes were part of a clever ruse to convince people he had perished, while the politician boarded a plane to Australia under a different name.

Because back in England, Stonehouse's life was falling apart. His businesses were floundering, a love triangle was threatening to destroy his marriage and his political career was in shambles after he was accused of being a communist spy.

With his house of cards just days away from collapsing around him, Stonehouse found himself inexplicably drawn to the other side of the world and the promise of starting anew with a clean state.

And he might have gotten away with it, had a twist of fate not brought authorities to his Melbourne hideaway a month later.

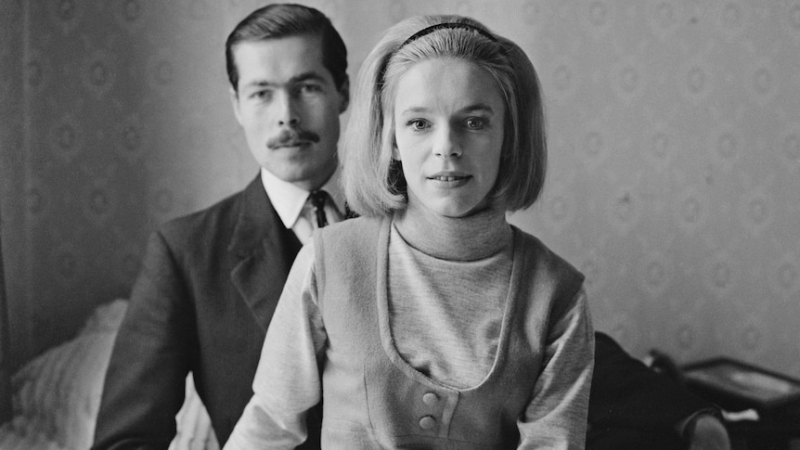

Police were searching for another missing fugitive, Lord Lucan — who was accused of killing his nanny and attempting to murder his wife — when suspicion fell on a man with a distinctly British accent withdrawing large sums of money at different banks.

The mystery of Lord Lucan turns 50

Photo shows John Bingham, dressed in a suit sits on a bed behind his future wife in a dress and sweater.

Instead of finding the titled peer, officers discovered John Stonehouse living in a nondescript home and using the alias JD Norman.

The British MP's disappearance and miraculous discovery exposed a complex web of deceit and followed years of rumours about his possible links to the Mafia, a Czechoslovakian spy ring and the United States Central Intelligence Agency.

"It is like an Agatha Christie novel — a very mysterious case," Robert Mellish, who was the Labor Party chief whip in the House of Commons, said at the time.

John was arrested on fraud charges and his subsequent trial gripped Britain, the nation transfixed by a high-profile MP caught trying to fake his own death.

But 50 years after his discovery on Christmas Eve, many conflicting narratives about his time in Australia have emerged.

In one, John was a man on the verge of ruin, who had found an escape in pretending to be someone else, only to fall victim to a disturbing mental disorder.

In the other, he is an ambitious con man who abandoned his family and orchestrated his fake death to escape the consequences of his actions and be with his mistress.

To this day, many facets of his story are disputed by authors, journalists and members of his own family.

All anyone can seem to agree on is that the only person who really knew John Stonehouse was himself.

The British MP accused of spying for a communist state

A second son from Southhampton, a port city south-west of London, John Thomson Stonehouse once dreamed of becoming a prime minister of Britain.

The child of left-leaning, working-class parents, he joined the Labour Party at 16 years old and became a trainee pilot for the Royal Armed Forces (RAF) before completing a post-national-service course at the London School of Economics.

Confident, charming and ambitious, friends and acquaintances nicknamed him "Lord John" for his lofty political goals.

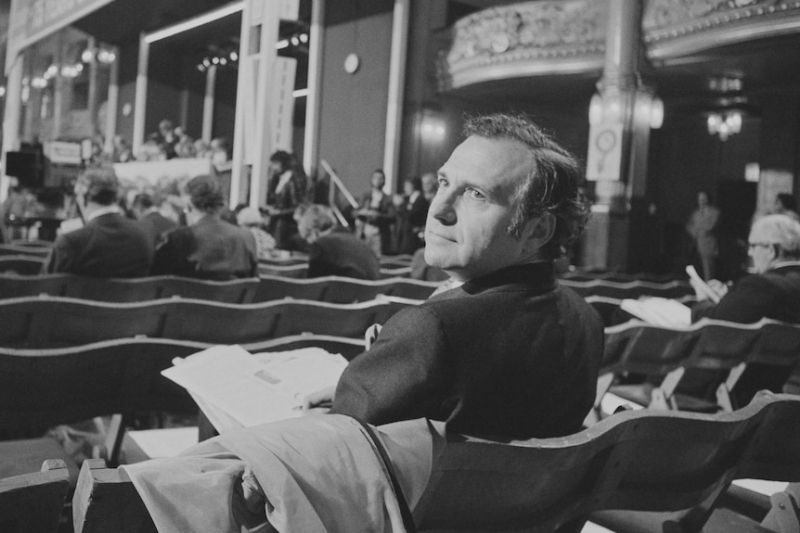

John Stonehouse was regarded as a rising star in the Labour Party and was once seen as a future prime minister. (Getty: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis)

He met his match in Barbara Joan Smith at a dance in 1947.

She was a beautiful, educated girl of 15 with similar political leanings and ambitions.

"You couldn't help but admire the way Barbara moved and lived," a friend once recalled.

The pair married a year later and travelled to socialist youth camps all across Europe, sharing their idealistic dreams and making influential connections, before moving to Uganda in 1952 to manage the African co-operative society.

Stonehouse returned to England with his wife two years later, brimming with progressive zeal but penniless and in desperate need of work.

He took up odd jobs until he was elected, aged 32, as the Labour Co-operative Member of Parliament (MP) for Wednesbury and Walsall North in a 1957 by-election.

The British politician quickly rose to prominence criticising the country's protectorates in Kenya as discriminatory and unjust, before reportedly catching the eye of Czechoslovakian agents.

It would mark the start of an alleged arrangement that would embroil the British MP in scandal and innuendo, though the exact nature of his involvement with Czechoslovakia remains in dispute.

According to Philip Augar and Keely Winstone, who wrote Agent Twister: John Stonehouse and the Scandal that Gripped the Nation, John was lured in with a splashy state visit and elaborate parties at the Czech embassy, before he was allegedly pressed for information.

"They psychologically groomed him over a period of time …," Julian Hayes — John's great nephew and author of Stonehouse: Cabinet Minister, Fraudster and Spy — told the Guardian.

"A Czech agent befriended him and worked on him over lunches and dinners. If they'd said, 'John, we'd like you to spy for us', he'd have said no. But a slow insidious step-by-step persuasion to cooperate worked."

The British MP had ostensibly agreed to meet with Vlad Koudelka, a captain in communist Czechoslovakia's secret police force, the Státní bezpečnost (StB), with the aim of twinning his constituency of Wednesbury with the Czech town of Kladno.

The arrangement was believed to be mutually beneficial to the two urban areas but Czech intelligence archives obtained by Mr Hayes reveal the nature of this relationship soon evolved into a spying operation.

John was allegedly paid 5,000 pounds in all ($AUD102,000 in today's money) for information about government plans and technological subjects, including aircraft.

In file 43075, reportedly buried in the StB archive, several documents in John's handwriting reveal his links to the Czechs, including a five-page report on members of the African National Congress.

"He was not a spy in the sense of James Bond or the novels of John Le Carré. But he provided the Czechs with information and got a lot of money from them. He knew what he was doing," Mr Hayes said.

For many years, no-one around John knew about his involvement with the Czechs.

"He was a complete loner," one parliamentary colleague told Time.

"I don't think he had a single close friend in the House."

Within the Labour Party, he was regarded as a rising star, having quickly climbed the ranks to become minister of state for technology.

In 1968, Stonehouse was promoted to postmaster general, where he introduced Britain's first and second class mail system, and then he was appointed to another privileged position, the Privy Council — a body of advisers to the Queen.

But his dramatic ascent would come to a halt in 1969, when Czech defector Josef Frolik claimed that John had been recruited as an informer.

Then-British prime minister Harold Wilson denied the rumours and the Czech exile's accusations were investigated by an inquiry, which found they could not be substantiated.

Harold Wilson was prime minister of the United Kingdom between 1964 and 1970, and 1974 to 1976. (Supplied: UK Parliament)

(Separately, Mr Wilson also rejected claims Stonehouse was a CIA agent, a bizarre theory that was also denied by US sources to the New York Times.)

John's daughter, Julia Stonehouse, has also denied her father worked for Czechoslovakia and has claimed the "spy narrative"' rumours were spread by right-wing elements of MI5.

"My website is called 'So where's the evidence?' precisely because nobody has been able to produce evidence [my father was a spy]," she said.

Even so, the Czech defector's allegations were damaging to John Stonehouse and when Labour lost the 1970 election, he was booted out of the shadow cabinet.

It would come to light decades later that former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher had agreed to a cover-up of information that confirmed he had been a spy.

He is believed to be the only British politician to have acted as a foreign agent while a minister.

With his political ambitions shattered, John became more preoccupied with his business dealings, starting his own financial institution called London Capital Group (LCG).

In 1972, he also took up a role as chairman of the British Bangladesh Trust, which involved setting up banking services and investment opportunities in Bangladesh.

But the venture went south when the market collapsed, threatening to take the money John had funnelled through along with it.

At the same time an ongoing affair with his secretary, Sheila Buckley, who was recently divorced and 21 years his junior, was threatening to blow up his marriage.

An elaborate fake death in Miami and escape to Australia

Before John Stonehouse made his fateful trip to Florida, his wife had set up a series of large life‐insurance policies for him and the children.

The policies were reported to be worth upwards of $US200,000.

Barbara Stonehouse later claimed the timing was pure coincidence, and was the result of a string of attempts on John Stonehouse's life.

The previous summer the British MP's car was blown up by a bomb and another was found in an adjoining house in London.

The real danger to Stonehouse's life, however, was himself.

After getting off the plane in Miami, Stonehouse checked into a hotel and talked with officers of a local bank before telling his business partner he was going to take a dip in the ocean.

Witnesses claimed they saw him walk over to a beach hut, put down his clothes and strut off to the sea in his bathing trunks. Then he disappeared without a trace.

Stonehouse had indeed gone for a swim that day, but had chosen to exit the water further down the beach at a neighbouring hotel, where he had left a change of clothes, money and a passport with his new identity.

Then he took a taxi to Miami Airport, where he retrieved a large suitcase and a leather briefcase before boarding a plane with a British passport in the name of Joseph Markham.

He flew first to Hawaii, embarking on a roundabout trip that took him to Singapore and Denmark, before he finally arrived in Australia through Perth on December 10.

John had used the forged passports of Markham and another dead constituent, Donald Mildoon, to travel around.

He may have finally been free but in Miami, Stonehouse's disappearance, which had initially been ruled an accidental drowning, was under a cloud.

When his body failed to wash up after 78 hours, police became suspicious. Normally, those who drowned at sea were discovered within a couple of days but there was no trace of Stonehouse anywhere.

They began to suspect foul play and a new working theory emerged that John Stonehouse was likely still alive, possibly being held prisoner by gangs.

The theory was given more prominence when Miami police found traces of blood and hair inside a "concrete overcoat", a signature method of Mafia burials.

His wife, however, was convinced he had drowned at sea.

"I've heard some extraordinary rumours and they're all so much out of character with my husband's personality that they're just not worth answering or worth thinking about," she said.

"I'm convinced in my mind that it was a drowning accident. All the evidence that we've had points to the fact that he was drowned."

Barbara Stonehouse believed her husband had likely drowned in Miami after he was reported missing. (Getty: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive)

While Barbara mourned her husband of 20 years, John was busy building a new life in Australia, depositing cheques and arranging for his mistress to come live with him.

It was his forays to town that first drew suspicion. A watchful employee on his lunch break noticed John Stonehouse going in and out of different banks with large amounts of cash and alerted his manager.

The police were contacted and the missing man was picked up by officers on a train to St Kilda on Christmas Eve.

Stonehouse was accused "of being an illegal immigrant with a false passport" and interviewed by police, where he admitted that he had entered Australia with a stolen identity.

A phone call to his wife, which was secretly recorded without his knowledge, would confirm his elaborate lie.

"Hello darling. Well, they picked up the false identity here. You would realise from all this that I have been deceiving you. I'm sorry about that, but in a sense I'm glad it's all over," he told her.

Shortly after his arrest, Stonehouse said in a message to the British prime minister that he had fled because of "incredible pressures" in business and "various attempts at blackmail."

"I suppose this can be summed up as a brainstorm or a mental breakdown," John said.

"I can only apologise to you and all the others who have been troubled by this business."

He would later argue at trial that his decision to runaway was brought on by an acute mental illness, and that his new personality was convinced he would be better off leaving his old one behind.

At first, Barbara Stonehouse believed him, describing his disappearance as a strange episode likely prompted by a disorder.

"It is not John Stonehouse as he is basically," she said at the time.

But officers believed John Stonehouse had been planning his escape for some time.

The police in Australia said his passport, bearing the name JD Norman, was issued in London on August 2, 1974, months before he disappeared from a Miami beach.

He had also spent some time rehearsing his new identity, assuming the characteristics of a "private and honest individual", before making his escape, according to a psychiatric report conducted shortly after his arrest.

Colleagues described John Stonehouse as a "bit of a loner". (Getty: Roger Jackson/Central Press/Hulton Archive)

In fact, Stonehouse may have been inspired by Freddie Forsyth's 1972 novel, The Day of the Jackal, which follows the story of an assassin who steals the identity of a dead child.

The Jackal searches gravestones in a cemetery looking for a birthdate similar to his own so that he can obtain a birth certificate and use it to assume their identity to apply for a passport.

But unlike the Jackal, John Stonehouse was no master of disguise.

The fraud trial that transfixed a nation

By 1974, most of Stonehouse's companies were in varying shades of trouble and the British MP was veering towards a financial cliff.

A wine company that he owned called Connoisseurs of Claret, Ltd had lost more than $US100,000 — equivalent to more than $A1 million today — in a single year.

Another of his businesses, a trading company Global Imex, was forced to close its office in Bangladesh and the managing director resigned, claiming he was owed money.

But it was a quasi bank called London Capital Group (LCG), which John had started two years earlier in the hopes of cashing in on a property boom, that appeared to be in the most difficulty.

Attracting investors and customers to LCG had proved trickier than first thought and John had eventually resorted to deceptive creative accounting to keep the business afloat.

That eventually attracted the attention of the Department of Trade and Industry and Scotland Yard.

According to the New York Times, Stonehouse had set up 24 accounts at 17 banks and passed checks involving hundreds of thousands of pounds.

He was eventually tried on 21 charges of theft, fraud and deception involving more than $US382,500.

Six months after his arrest in Australia, Stonehouse and his mistress were flown from Melbourne back to England under the escort of four Scotland Yard detectives.

He was granted bail and continued to serve as an MP while he awaited his court case, telling colleagues he had suffered a complete mental breakdown.

"A new parallel personality took over — separate and apart from the original man, who was resented and despised by the parallel personality for the ugly humbug and sham of the recent years of his public life," he said.

"The parallel personality was uncluttered by the awesome tensions and stresses suffered by the original man, and he felt, as an ordinary person, a tremendous relief in not carrying the load of anguish which had burdened the public figure."

Stonehouse represented himself at his 68-day trial and was ultimately found guilty of forgery of a passport, stealing cheques from his own company and attempting to defraud insurance companies by pretending he had drowned.

He was found innocent of one — conspiring to defraud creditors.

Sheila, his mistress, was presumed to be an accomplice in his conspiracy to deceive. She was, however, given a suspended sentence when a judge decided she'd been controlled by her boss.

Sheila Buckley began an affair with John Stonehouse before he faked his death in Miami. (Getty: Keystone/Hulton Archive)

In 1976, John was sentenced to seven years' jail but only served three before being released on parole.

John Stonehouse's legacy and the women he left behind

The mystery and intrigue of John Stonehouse and his fake death continues to captivate audiences decades after his arrest.

Books, podcasts and, more recently, a television show have set out to unpick the bizarre details of his disappearance and escape to Australia.

But the truth about what prompted his disappearance is likely buried with John.

What is undeniable is the impact it had on those he left behind.

Barbara Stonehouse had initially stood by her husband after he was discovered in Australia.

"The moment he put his arms around me and kissed me, I forgave him," she said.

"I realised that despite this terribly selfish action of his, I loved him still. And so it is."

But as the details of his treachery were revealed at his trial, it took a toll on her and she eventually left him.

"I am recovering from the shocks of the past months," she said.

"I can get by very well in life. I am going to support myself. I am going to carry on with the firm I've been working for as a public relations consultant."

The pair divorced in 1979.

Meanwhile, after his release from prison, John Stonehouse wrote three novels, all thrillers, and married his mistress Sheila in 1981.

While in prison, Stonehouse suffered three heart attacks and underwent open heart surgery.

He later died of another heart attack, at 62 years old, just as he was preparing to give a television interview about his fake death.